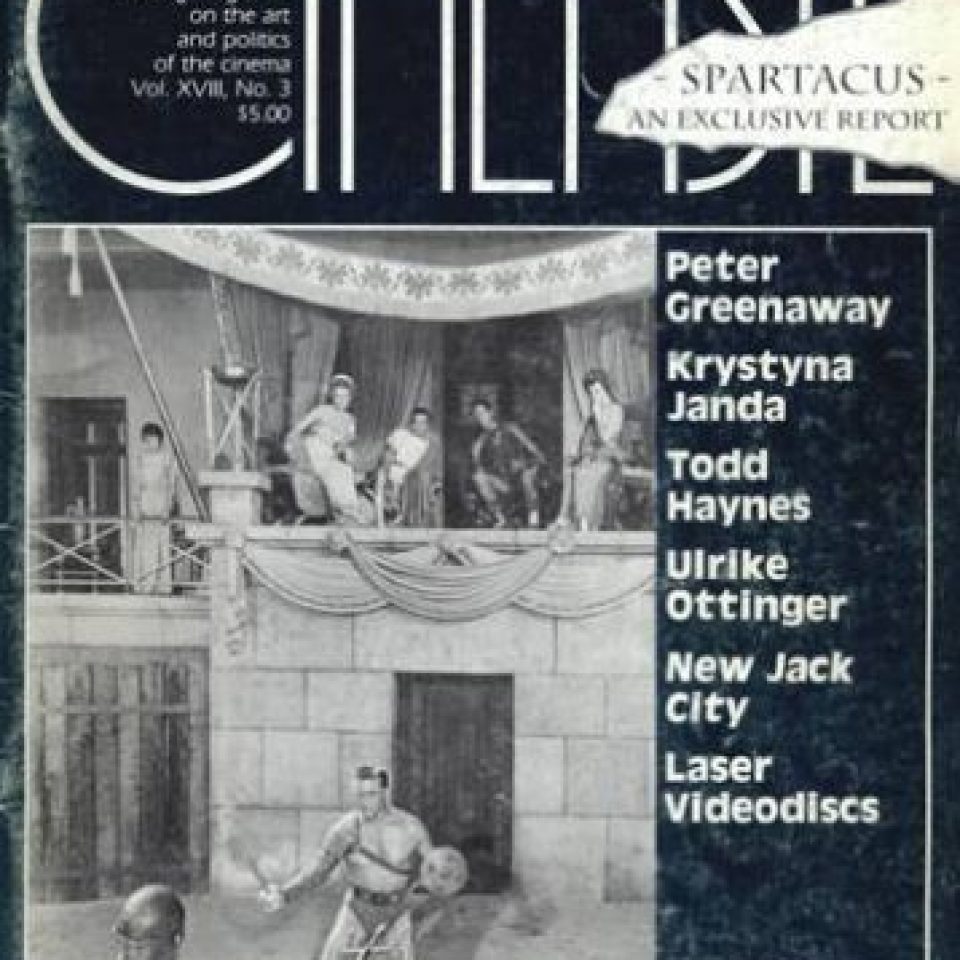

AN INTERVIEW WITH KRYSTYNA JANDA

Woman of Marble

AN INTERVIEW WITH KRYSTYNA JANDA

by Michael Szporer

CINEASTE, Vol.XVIII, Nr 3 z 1991r.

Krystyna Janda is one of the leading Polish actresses of her generation. Born in Starachowice in 1952, she studied at the College of Drama in Warsaw, and made her remarkable film debut in Andrzej Wajda`s Man of Marble (1977), one of the most signyicant films made in postwar Europe. As Agnieszka, a student at the film academy who brooks no obstacles in her determination to complete a documentary on a Stakhanovite hero of the Fifties, no matter what unpleasant historical truths it may expose. Janda forged a gutsy, independent new model for screen actresses, with critics dubbing her the “Woman of Marble.” Alternating between film and theatre work, Janda made subsequent appearances in three other films directed by Wajda – Without Anesthesia (1978). The Conductor (1979), and Man of Iron (1981) – as well as Istvan Szabo’s Academy Award-winning Mephisto (1981). For her powerful performance in Ryszard Bugajski`s Interrogation as a falsely imprisoned cabaret singer who resists Stalinist terror (see review in Cineaste. Vol. XVII. No. 4), Janda won the Best Actress award at last year`s

Cannes Film Festival.

Cineaste: Your screen roles have made you into a symbol of the rebellious generation that signaled the beginning of the end of the Soviet empire. I suspect that with this image comes a good deal of responsibility to the public. especially now in the new Poland.

Krystyna Janda: Times have changed. Of course. I cannot spoil the image which Andrzej Wajda has created and I still have to be careful about what I play, what I say, and with whom I work. In this respect. I have to act responsibly. I wouldn`t want to destroy that image because it would simply be a shame. On the other hand. I can now develop creatively in other directions. I can play comic roles, perhaps even in comedies about martial law. I can relax a bit and laugh. I can play roles like the one in the TV mini-series Modrzejewska or be completely apolitical as in the role of Giselle in Two for the Seesaw. Before I rejected many roles, even roles which, as an actress. I really longed to play, simply because I had to live up to my image.

I think I`m a `natural` when it comes to acting and occasionally I regretted holding back. There were times when I yearned to walk down the aisle in feathers with the other show girls, or to sing, or to play something totally stupid. People proposed excellent roles for me that were not my `type` and I had no choice but to reject them.

I also had to watch what I said in public and even in private. When I made a TV appearance, I had to be very careful. Even when I went out in Warsaw or said something at a private party, I ran the risk of being called in and interrogated. This actually did happen to me once after I told a couple of jokes about the ZOMO [paramilitary police units-M.S.] at a party. But living up to my screen image was actually quite uplifting: it wasn‘t like I sinned. Now I am still careful. Please don`t misunderstand me. I`m willing to put my own signature to anything I’ve said. I never said anything I didn`t agree with. But now I can also be an actress in the wider sense of the word. I can play negative roles, or permit myself to splurge a little.

Cineaste: You have been called not only the icon of Solidarity but also of the emerging feminist consciousness in Eastern Europe. What makes your roles really attractive is this feminist sensibility which is really quite unprecedented in Polish film. You play very decisive women fighting not for some stereotypical set of values but for a deeply human individualism. You play strong, determined, independent-minded, and, above all, thinking women. How do you see your energetic activism on the screen as reflecting what Polish women today think?

Janda: I really believe that this strength of character comes from our tradition. ln our literature or other forms of cultural expression, women are much stronger than men. The woman in her role as the mother figure is certainly cherished. In contrast, all our Romantic male heroes fail. They have their weaknesses – they want to kill the tsar but catch fever, Kordian, Konrad, Gustaw – they are all weaklings. These men have terrible doubts and problems. The women, even though they don`t play principal roles, are really the ones who endure, who wait, who suffer, who really make do under trying circumstances. Women are marginal but strong. There are no winners in our tradition as far as the hero is concerned but the women hold their own.

I`ll tell you a funny story about my positive role. When Andrzej Wajda first gave me the part in Man ofMarble, he told me that in whatever I do, I had to enchant, anger, or Irritate, because I had to carry half the film. And about my being up-to-date-several days later, he said, „Damnit, Americans are making films with just men. What the hell am I doing working with a woman? Can you do it like a man?” And I said, „I’d be happy to,” That joke started the ball rolling. I suspect at some point Andrzej realized that I behaved on the screen without much thought; I acted on impulse, by instinct, because I knew such girls in my crowd. I blew them out of proportion a little but the role was real. It took awhile. but Andrzej sensed that aggression. that self-confidence, that dynamism and that fortitude as an expression of new thinking, and he understood that there was a chance to show this emerging ethos on the screen. He told me that my role should announce to the world: „Watch out. here comes a generation that will not only open doors which were closed for so long. It will force them off their hingers.” And he was absolutely right because my age group created Solidarity. He deliberately exploited my behavior and my personality to forge a new idea.

No woman before acted like that in our films; such a role never existed. In Man of Marble, there is not a single moment when I am self-involved. Aside from a brief scene with my father when I express some personal doubts, I don`t think about myself. I`m always forging ahead, attacking the matter at hand, pursuing an idea, taking care of someone else. I move forward. I make the decisions. This determination was a real innovation. Until Man of Marble, women in our films were flowers to look at and admire. They just floated across the screen and really didn`t hold power.

They were self – involved, not other – involved. I really have to credit Andrzej with validating that determined woman who was in me – for telling me that`s how it really ought to be.

And then, it was sheer luck that Ryszard Bugajski wrote a scenario that explored this positive figure from a woman’s point of view. Immediately after reading it, I realized I had the opportunity to create a hero that was virtually nonexistent could not be beaten – the totalitarian system. Tonia triumphs by very simple means – by sticking to her testimony and her personal dignity. Nothing more than that. I understood I could show everyone in the audience that even they could beat it. Of course, many people watching probably went through far worse and many of them were bigger heroes than Tonia. Neither Bugajski nor I were really exaggerating – I had the right to play that girl for them, to give them hope, especially the young.

The young have absolutely no idea. They take E.T. as truth but they come out of Interrogation saying. „No, this couldn`t be. This isn`t true.” They can`t believe that such Things, or far worse, actually happened. The younger generation doesn`t understand or want to know that that`s how it was in the old police state. This is why Ryszard`s film was so important to us and why I had to create a role which would reach even the fourteen-year-olds. That`s why the film has certain hues that seem improbable to those who lived through it. But we were making the film with the new generation in mind – to get to them. I had been told that if this role was played by an older actress who remembered the times or lived through them, she would not have been able to bring herselfto such displays of triumph, to be so clear – cut in this particular role. It had to be done by a different generation. So we return to the point we discussed earlier – that only my generation could slap the face of the system and throw things out into the open. The older generation was much too self – conscious and carried too much pain inside. So everything hinged on a character who was drastic, who followed through on her actions, who had optimism, who was above all effective and clear about where to go and what to do, who could not be distracted and would never look back.

Cineaste: Do I detect a deep ferninization in this emerging vision, an antipatriarchial quality that accompanies antitotalitarian thinking?

Janda: Sure, in retrospect, but was it really intended? If they found a man like that, they probably would have used him. But such a man didn`t exist.

Cineaste: Interrogation really is afilm about women. Do you think Bugajski has a special interest in the concerns of women?

Janda: Yes, this is very unusual. There are few directors who can take the womans point of view. Films are mostly made by men and about men.

Cineaste: You play strong, unbreakable women. Nonetheless, when one contrasts Agnieszka of Man of Marble and Man of Iron with Toni of lnterrogation, they are very different women. One is an intellectual who looks for her roots, who uncovers the secret history of her nation.

The other is a rather ordinary woman who does not allow herself to be broken and struggles for her dignity without giving it much thought. She is not fighting for everyone, only for herself. The film has very little to do with ideology. Which of these roles is closer to you personally, which came more naturally?

Janda: It`s very difficult for me to respond to this question. I think that Agnieszka was closer to me at the time because I couldn’t play or construct anything other than what I understood and knew, and my knowledge of the Fifties then matched Agnieszka’s – zilch! I learned as I learned the role. The heroine of Interrogation came after

nearly nine years of acting when I was capable of constructing a role and choosing the most effective means to achieve a specific end. Interrogation is really a fantastic idea for a film – starting with a person without any ideas or convictions, who is oblivious of the political system she lives under. That initial innocence really appeals to the spectator. Here is a blank sheet of paper that literally writes itself in front of our eyes. You experience her growing awareness. But Tonia was staged by me. Agnieszka was really me; Tonia was me the actress creating a role.

Cineaste: So you grow with your films… become more of an activist?

Janda: Of course. My development is obvious in Man of Iron, which came four years after Man of Marble. My Agnieszka changed, that is to say, I changed along with Agnieszka. For example. I knew Agnieszka wouldn’t enter the shipyard, I knew that, as a woman. I should stay with the child. We considered for a long time whether I should participate in the strike. And Andrzej said, „No, because now you have to make yourself over into another symbol -the mother who protects the future. Because that`s how it ought to be. And you have to play it like that. This is already the next stage in the historical development.”

Cineaste: And then came Interrogation, another stage in the development.

Janda: Yes, Interrogation looks at the problem in yet another way. That it’s a woman this time makes it easier to tell the story. Using a woman made the experience more painful. If the point of view was of a man, it would have been told differently. A woman enabled us to explore the human frailties and to introduce playfulness into the part that would not have been accepted otherwise: using a woman gave us more flexibility. A man could not have experienced such moments of weakness and maintained audience empathy. Also, the story was really based on the lives of two real women who lived through the Stalinist hell: Tonia Lechmann and Wanda Podgorska, the secretary to Wladyslaw Gomulka [former Communist Party Secretary – M.S.] Mrs. Podgorska, who spent six years in prison, including two in an isolation cell, served as my consultant on the film. She told me what I could and could not do, how impudent I could get and what I could get away with, or how playful and still be tolerated. We had to make sure we documented the film very well because we had to defend everything we did in front a review board. That is why the French reaction at the Cannes festival showing, that the film was unreal, made me angry. It was remarkably factual.

Cineaste: Your key roles have been in films about the Stalinist period. Would you agree that the dwerent ways in which Wajda and Bugajski portray the period

reflect the viewpoints of two dwerent generations? Wajda shows us a slice of history, a bildungsroman of working class consciousness: his approach is more rational, an attempt to fill in historical gaps. Bugajski shows us the fragile, human side of this reality.

Janda: Yes, he proceeds from detail to gestalt. However, one shouldn`t forget that Andrzej ‚s film was really a mile – stone, the first to deal with the Stalinist period. It had to be done that way. It breached a taboo subject. It opened the door for films like Interrogation.

Cineaste: I understand, but that doesn’t take away from the contrast. Bugajski’s film gives us a slice of life of those times: it is really a period piece exploring a human tragedy in a deeply personal way. Do you think the differences in vision can be explained by the generational gap?

Janda: That`s likely. Or perhaps it is Wajda’s personal style. He has a real flair for the social, for being a ‘social activist, a label which in Poland is sometimes used pejoratively. He envisions himself in the role of the teacher of the nation. Ryszard simply made a film about a detail that appealed to him, while Andrzej knew that he was making one of the most important films in the history of our cinema to raise the consciousness of a new generation that had no idea about Stalinism. Fully aware he was dealing with a taboo subject which couldn’t be discussed or written about, Wajda knew he was making history. I suppose you could take it as a generational trait, but I really think Andrzej simply has it in him, that flair for the master – piece. That’s why he made The Wedding, The Shadow Line, The Promised Land – all these films hit a high note.

He likes grand gestures. Ryszard picks up a detail which appeals to him and, if it strikes a deeper chord, that`s another matter. He didn’t make much of it. He was looking at the Fifties from the vantage point of a new generation that looked at it as interesting history. Andrzej thinks in terms of the big picture while Ryszard gets it out of the details. For him the Fifties. nine years after Wajda, was a known quality. He knew he was making a film for people who knew what it was about. Andrzej’s film for my age group was a real eye -opener. He started with the ABCs and taught us letter by letter.

Cineaste: How has making films under the pressure of censorship changed now? Interrogation was one of the first Polish films made without censorship.

Janda: Yes, it was one of two films made without permission from the censor, without submitting the scenario for review, during those eighteen months of anarchy when

we were free to do anything we wanted. And we hurried to finish before the situation changed.

Cineaste: And it was actually edited during martial law.

Janda: When we were making it, I couldn’t believe we were making it. that it was possible to do it. Eighteen months was not a whole lot of time to get used to the idea that it was possible. We thought perhaps we were mistaken. When I look back at this role and review nine years later how I acted (Interrogation was shelved in 1982 and released on December 13. 1989-M.S.), I suspect if I were doing it now, I would reflect on it more. I would construct it more carefully. I know much more now. But then and there, with the growing realization that happened so suddenly – that it was possible to do it – it was a sudden outburst of hate. I gave myself completely over to that brief scream without really reflecting on it.

I guess what I am saying is that I was really a faithful child of that nightmarish system, a good girl who went to that school, watched that television, read those books. attended those military defense classes – who diligently studied Poland, the Fatherland, the road to communism, and so on. Oh, I was such a good student and so carefully indoctrinated. Only a person like that, who comes to a realization what has been done to her, could possibly generate such an outburst of hate. Today, I would try to balance the sides, I would wonder whether it wasn`t too rough, whether it wasn’t too much. At that time. I didn`t think, I simply screamed. We all did. It was as if we found water after being in the desert for twenty years. I remember that we filmed on Sundays, at night, impossible even in Poland. On this film, no one objected, from the lighting engineer to the stand – in. It didn ` t even enter our mind. „On Sunday, hell let it be Sunday!“ Everyone knew we were doing something unprecedented, something never done before. We knew we had to do it as fast as possible and as good as possible. How we used to argue, how we used to yell at each other. By the end, we didn ` t talk normally, we just screamed. Never before in my life had I made a film in such an atmosphere.

Cineaste: Can you imagine a situation where lack of censorship can be detrimental to a film? It has been said that censorship contributes to suggestiveness and symbolic texture. By contrast, Interrogation has none of that. It strikes me that your role in the film was without any make – up and Bugajski `s film is very raw. It has a documentary look.

Janda: There is something to what you say. There was a time when Polish audiences knew that certain subjects were taboo, so, when it was possible to get something past the censor with a wink, it was all the more satisfying. Those who made films and those who watched them were in a conspiracy against a common enemy. For someone looking in from outside, the audience reaction must have seemed puzzling. Everything was based on this esthetic of winking the eye and looking for a deeper meaning. Now this is over; we have to reestablish real norms, but it `s not easy. Several directors told me they are unable to make films without censorship; that thrill of suspense, that added edge of putting somebody in confidence by some oblique means has vanished.

I remember Andrzej Wajda once started making a film about priests and met with an even worse censor in the church [laughs]. So he dropped the project after a week – you can ` t do this and you can ` t do that. It was an excellent idea with something about Solidarity in it. But he reflected: if it was allowed, then there was no reason to make the film. He dropped the project because he realized that only in our sick system would such a film have any real value. A film is made because you can `t make it but , if you could, would it be worthwhile? Many people today have serious problems making films in a world without censorship. We don ` t know how to make other films yet.

Cineaste: For years, artists here have been tn opposition to the regime. This has recently changed. A maverick a dissident, is suddenly „official“ in post – Soviet Poland. What psychological effect has this new order on the artist and her creative abilities? How are you coping with being „establishment“ ? Can you be critical or might it be construed as blasphemy? Do you foresee a cabaret about Walesa in the near future, for example? And does this changing situation bring about new uncertainties a new form of self – censorship or even a new tendentiousness of some other kind?

Janda: You hit on the most perplexing problem confronting the artist in Eastern Europe today. That is, the cabarets are down and nobody really knows what kind of films we ought to be making. No one would dare yet, no one has figured out how to make a comedy about such subjects as martial law, which is what the audience really wants.

The audience is way ahead of the artist. The letters I receive from fans are precisely about that – they want comedy, they want us to laugh at ourselves. Unfortunately, we are still not up to it. Yet it is the first duty of the artist to be in the opposition. But whom to mock? Not the current government they haven ` t had enough time yet; not the old regime, that `s already a low blow. No one knows what to do. I read a lot of scenarios by young people and they either still want to dwell on the Fifites, which nobody wants to see, or on martial law, which everyone has seen, or do science fiction or ballroom dramas and that `s it. They are incapable of doing anything else because they haven ` t gotten used to the new times to telling real stories about real people. I have not read a single scenario recently in which I want to act. Nothing has genuinely moved me. Not one of these scenarios has struck a chord I ` m certain the audience wants to hear. What ` s more, a lot of artists are suddenly in politics. This is a transitional period but I `m really banking on the very young, on those who are just beginning. They will strike that new chord and set a new tone for our cinema. Some hopeful signs are

already there – for example, the young director Marek Koterski who made the film Madhouse and who recently wrote a play, Teeth, a comedy that mocks all our national sacred cows and which no theater is courageous enough to put on. He might be an early swallow before the oncoming storm.

Cineaste: In your opinion, is art in Poland today completely free or is some new ideological hue taking shape? And what about the new economic conditions how will these affect filmmaking’?

Janda: This is a very difficult question since filmmaking here is really being restructured from the ground up. No one is in the position to say what will be its future, or, more concretely, to predict what will happen to the industry when government subsidies run out in 1991. Can film survive without subsidies? The most catastrophic picture of what might happen already exists for writers and poets, since some books will now not be published and some are not even being accepted. No one knows how to finance them. Many theaters are likely to be disbanded and there might be only two or three left in Warsaw. Who will play in them, no one knows. Our situation reminds me of a woman past her prime who is powdering herself and doesn ´ t want to admit she is getting old. Everyone seems to be pretending they don ` t see the writing on the wall. We had time to reorganize but it `s running out. As for the audience, it doesn ` t want to see us as sickIy, poor, ugly, and bad, but as beautiful, rich, and happy. But no one thinks that way yet. I think young directors already understand that if they really want to do something, they will have to go abroad and find money, then come back and shoot their idea here. But then these ideas, these themes, must be international, European in scope. They can `t be narrowly defined by our local problems.

We won awards because we were different. Our cinema until now has been completely involved in our internal problems which the world outside didn `t understand but which we tried to show, sometimes so feverishly and with so much passion which they have long forgotten possible.

Interrogation is a very hot statement which must have been a shocker to anyone looking at it outside of Poland. Even when they raise serious questions, films made in the West are smooth, pretty to look at, and, by comparison, much easier to digest. When Interrogation was shown at Cannes it must have seemed like hysteria, particularly after the collapse of the bloc. No one was quite sure how to take it: whether to dislike it, to be angry, or to take slight offense. Some well – known producers with a number of excellent films to their credit came out of the showing with the habitual, „Thank you for a most enjoyable evening“. No, I don `t expect to always be known for political films. Not all my roles have been political and our situation has changed. But the police state terror was very real and films like Interrogation are not just fairy tales of horror. What we showed wasn `t pretty but it was true.

Michael Szporer `s translation of Ryszard Bugajski `s script for Interrogation appeared in New Orleans Review. Vol. 16 No. 2 (1989). Janda `s latest film to be released in the

U. S., lnterrogation is distributed by Circle Releasing Corporation. 2445 M

Street. N. W., Washington. D. C. 20037. phone (202) 331 – 3838.